Of all the geopolitical and geoeconomic headwinds facing the Middle East and North Africa, youth unemployment is the most pressing.

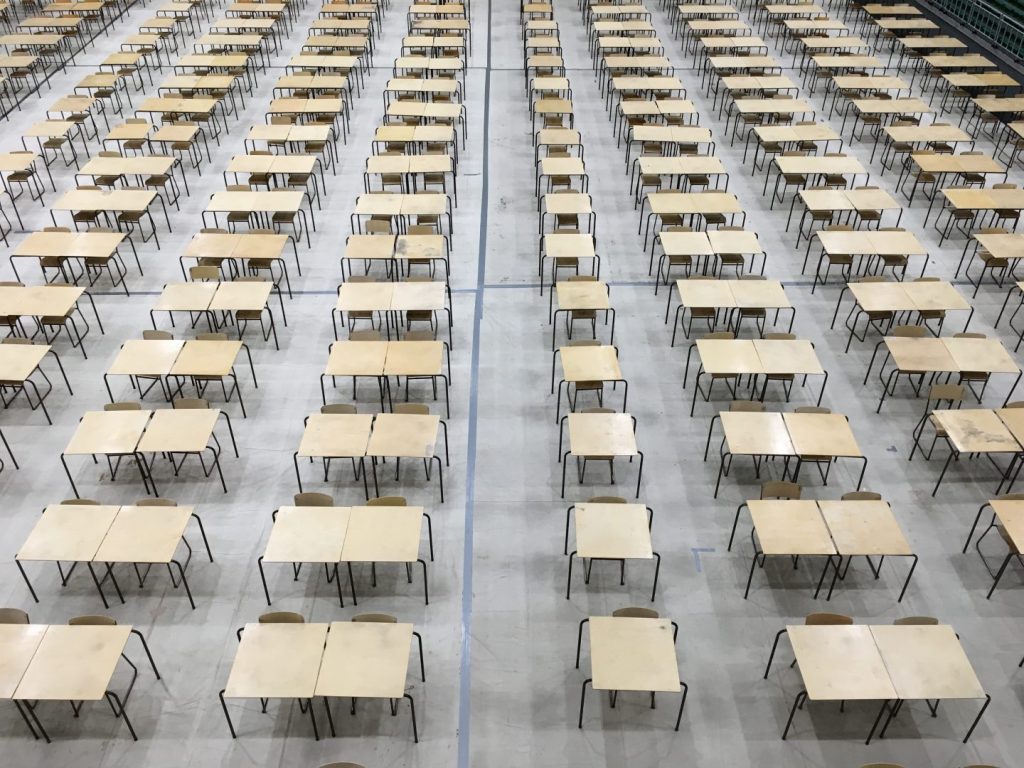

At 30%, the Middle East and North Africa suffers from the highest youth unemployment rate in the world. The region’s states need to create approximately 100 million new jobs in the next 10 years to address current unemployment as well as accommodate new labour market entrants. Lower oil prices are severely constraining the ability of the public sector, traditionally the region’s largest employer, to absorb these new entrants.

At 30%, the Middle East and North Africa suffers from the highest youth unemployment rate in the world. The region’s states need to create approximately 100 million new jobs in the next 10 years to address current unemployment as well as accommodate new labour market entrants. Lower oil prices are severely constraining the ability of the public sector, traditionally the region’s largest employer, to absorb these new entrants.

Therefore, long-term sustainable job creation must come from the private sector. In this context I was delighted to have the opportunity, at last year’s STEP Conference in Dubai, to interview Fadi Ghandour, founder of Aramex and one of the leading advocates of private sector-led development and entrepreneurship in the region, on how exactly the employment challenge in the MENA region can be addressed.

First, it is important to understand how relatively small cultural shifts can lead to large, outsized outcomes. For instance, the IMF has calculated that increasing female labour force (FLFP) participation to the level of males across the region, could create as many as 58 million jobs – almost 60% of the target requirement over the next 10 years. Whilst this target may be unlikely, any increase in the FLFP rate will have a significant positive impact on employment.

Second, private sector investment in education will be critical to reforming curricula and ensuring today’s students graduate with the key skills they need to be competitive in the global workplace. This is creating enticing opportunities in education for investors willing to take a long view. Demand for quality education from anxious parents concerned about state provision is soaring and expected to quadruple, reaching $20 billion p.a. by 2020. The number of private schools in the GCC alone is expected to double resulting in more than $55 billion worth of education projects.

GEMs, a private education provider, has been building schools and investing in education for 30 years. It now runs an extensive and profitable regional and global network of schools catering to all price-points, earning 20% profit margins on a range of its private schools. Alghanim Industries, the Kuwait-based conglomerate, funds a 9-month classroom-based and rotational development programme to equip students with key marketplace skills and guarantees those who graduate, a job.

For businesses considering brown or greenfield investments in the Middle East and North Africa, tackling these institutional voids by offering services outside of their core offering, such as Alghanim has done, should form a key part of their market entry strategy. Companies doing this can develop critical relationships with key government stakeholders. For instance, Samsung has begun preliminary discussions with the UAE government to “reverse design” school curricula, ensuring students attain a specified skill set

by the age of 18 relevant to their industry. Developing human capital is clearly a win-win strategy for companies and countries alike, and the private sector, beyond traditional education providers, can play a critical and profitable role in developing the human capital the region needs to be competitive in the global market place.

Third, whichever way you look at it, entrepreneurship will be at the centre of job creation – and the MENA region has a lot of start-ups that are maturing rapidly. Just over a year ago, Talabat, the Kuwait-based food delivery service, became the latest big exit, bought by Rocket Internet for $170 million. Amazon is reported to be in talks to purchase Souq.com for $1bn. Careem, the chauffeur service app, recently raised a Series C round of $60million led by Abraaj. The region has now witnessed over 40 major exits in the past 15 years, including Yahoo!’s acquisition of Maktoob in 2009 for $164 million. This has led to a steep maturing of the VC and angel funding environment. Over the past 5 years alone, the average fund size has grown from $15 million to $45 million. Dubai is now awash with diverse investors, including global players such as Rocket Internet and 500 Startups, international institutions such as the IFC and EIB providing private equity funding, as well as regional investors such as Beco Capital and Wamda Capital. Whilst Dubai has become the most well-known regional entrepreneurship hub, venture capital investors may find that now is an opportune moment to uncover promising start-ups at bargain valuations in other rapidly maturing start-up hubs, particularly in Cairo, Beirut, Amman, Tunis, Ramallah and Abu Dhabi. Global corporations already resident in hubs such as Dubai may wish to follow in the footsteps of some of their peers and consider setting up a VC arm to explore opportunities within their respective verticals. For example, regional telcos such as Zain, Mobily and STC Saudi have all set up ICT focused venture arms.

Furthermore, investors considering larger private equity investments, for instance in energy infrastructure and renewable energy projects, may also find a plethora of opportunities in countries in the Gulf, as well as in Jordan, Egypt, Algeria and the Palestinian-controlled West Bank. Governments are partnering with international development institutions and mature private equity players such as Abraaj to offset political risk with attractive output pricing guarantees. Saudi Arabia has set an output target of 9.5GW from renewables by 2022, which might be a particularly attractive investment proposition, bearing in mind that domestic energy consumption will continue to rise significantly, the new global energy context is forcing a diversification beyond oil and the Kingdom has the lowest solar production prices in the world. At current investment levels, the renewable energy industry will create 210,00 jobs by 2030.

In summary, whilst structural challenges in the Middle East and North Africa abound, investors and businesses will discover numerous lucrative investment opportunities by thinking slightly outside of the box. Understanding which institutional voids to fill will accelerate the building of key government relationships, which is critical for a company wishing to establish the right distribution network, identify the right partner for a joint venture, or be the first to uncover the next big start-up. Adopting this strategy will also serve to protect from political risk whilst bringing much needed private sector investment and know-how that the region needs if it is to fulfil the employment imperative and the hopes and dreams of its youth.